Introducing Packer

Portable Packer is a developer and packager friendly tool for, you guessed it, packaging. It is designed to operate based on modes specified by the packager. Within a few lines, you can create a completely new sandboxed package, potentially free from known escape exploits.

Why a new tool? You may ask. Hold the comments before I explain.

How packaging works for now

Let’s look how a packager create a new sandboxed portable app on Arch Linux. Take firefox-developer-edition-portable created by me as an example. It’s PKGBUILD looks like this before:

1 | # Maintainer: Kimiblock Moe |

Looks pretty straight forward, isn’t it. Let’s focus on the prepare() and package(). You first query all of the files owned by the original package via pacman -Ql, add some dependencies and install them via a while loop. For finalizing, the portable config is then installed, and the .desktop file is replaced.

Of course it works. All packages from the repository is packaged like this.

But, this is not we want. And it has several downsides as some of you might’ve already realized.

Great, what’s the problem?

Duplicated lines of packaging code

As Portable packages continue to grow in figure, we have tens of duplicated copies in the repo. Not only makes the whole repository messy, but it also becomes a pain when we have to change something in all packages. Yuck!

Simplify for Elegance

Please recall the PKGBUILD example linked above. And look at the heading: Simplify. Now the hassle of manually hand writing packaging commands is gone. What’s above is the same as this:

1 | function package() { |

Clearly this approach is much more elegant than before, and it handles heavy lifting by itself. Which is the design goal of Portable.

Let’s explain this line-by-line: The first 2 lines is exactly identical, as dependencies are still set by the packager. The difference begins at line 3.

- We export

pkgdir,pkgnameandsrcdirin the shell. This is done to provide packer with some information so you don’t have to include it manually (those are not exposed to child processes). - The Packer is called with arguments:

-vto enable verbose logging--distro archto use Arch Linux specific code--mode copy firefox-developer-editioninstructs Packer to enter copy mode, and get files from thefirefox-developer-editionalpm package.--hash truecurrently has no effect, but will be relevant in following Portable releases (stay tuned!).--config "${srcdir}/portable-config"specifies the configuration location for Portable.--desktop-file "${srcdir}/firefox.desktop"tells Packer to use that desktop file directly.

Much simpler huh. You might be able to understand it ten times easier than the previous approach.

With packer and it’s unified mode of operations, packaging becomes mostly abstracted to packer options. For most packages that copy files from the original one, you just specify dependencies, and call packer with a fre lines of options. This makes the whole packaging pain easier, and you won’t have to dig through docs to find out required operations.

Cheesy!

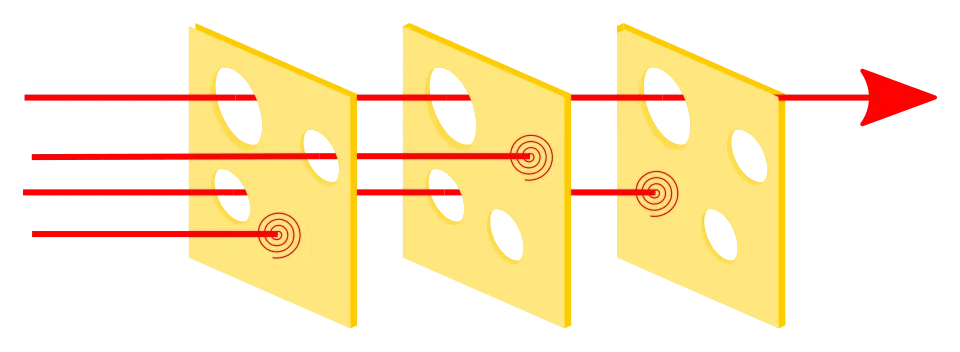

If you are into, or interested in Aviation like me. The Swiss cheese model may not be unheard of. Don’t worry as I’ll explain:

The Portable sandbox is like a stack of cheese slices. Every slice is a defence measure built to mitigate threat. Holes in the cheese slices represents weakness and error. Although we probably can’t eliminate all weaknesses, multiple layers of defences can be built to mitigate the threat, and prevent if from penetrating the security system (Portable).

Like all security defences, human is usually the weakest point of defence. There are too many of ways to break the sandbox: you may forget to remove D-Bus services making it instantly escape when anyone try to activate that interface, even unintentionally; there may be surplus binaries under /usr/bin; the .desktop file may not be removed beforehand and much more…

In a nutshell, a lot of things may go wrong. And many escapes are being found constantly. You might have no issues today, but next version there’s a hole you might forget to plug.

Packer is there to serve as an additional layer of security cheese. Therefore eliminating some portions of human error, preventing some escapes to materialize in advance.

Footnote

- The cheese model illustration is borrowed from Wikipedia author BenAveling, distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. The model was originally formally propounded by James T. Reason of the University of Manchester

- This is just a small part of the 11.0 release.